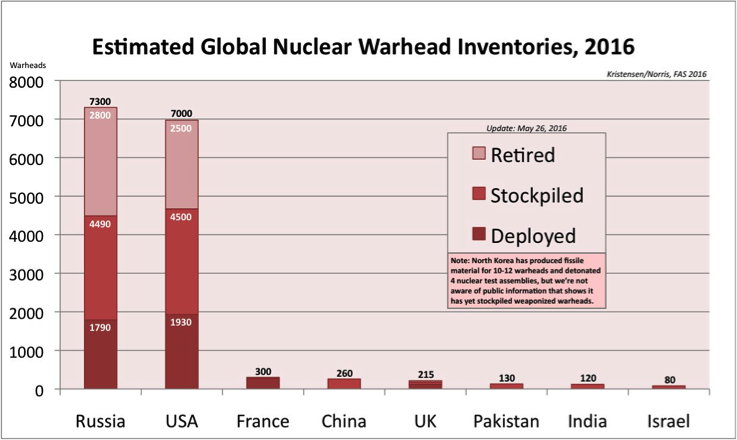

At this very moment, the United States and Russia are locked in a nuclear embrace. Our collective fates — and those of the rest of the world — are entangled in a mesh of ballistic missiles, nuclear submarines, and strategic bombers. Together, the US and Russia control more than 90% of the world’s nuclear weapons. When we talk about global nuclear stockpiles, we are overwhelmingly talking about the United States and Russia. The following graph [1] illustrates the profound asymmetry between their arsenals and everybody else’s:

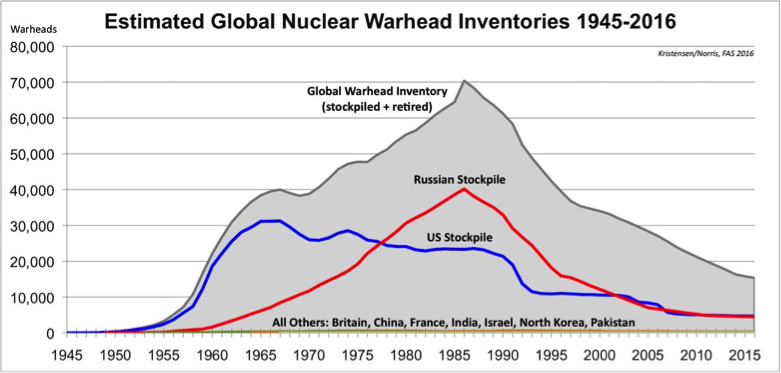

This staggering lopsidedness is one of the more grotesque legacies of the Cold War, when both sides built up nuclear arsenals with overkill capacities that seem patently absurd in hindsight. The disturbing thing is that the state of affairs sketched above is actually an improvement: the overall number of nuclear weapons on the planet has drastically decreased since the end of the Cold War. If you compare the current moment to the mid-1980s in the next graph, it’s immediately clear how much progress has been made:

At the same time, though, it’s also evident from the chart how much the disarmament trajectory has stagnated since around the time of the New START treaty in 2010. And while there hasn’t been any real increase in stockpiles, the remaining US and Russian warheads — more than 14,000 in total, about 3,700 of which are deployed — are more than enough to cause unparalleled destruction to our world and its inhabitants. Overkill still rules the day — and for no discernable reason. As disarmament historian Lawrence Wittner recently pointed out [2], even the Joint Chiefs of Staff have concluded we could drop down to 1,000 deployed nukes with no substantive impact on US national security.

So why then has progress stalled? Clearly the deteriorating relationship between the US and Russia is largely to blame. In just the past few years, the two countries have been at odds over the pro-EU demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, the annexation of Crimea, the Syrian Civil War, NATO missile defense systems in Romania and Poland, Russian missiles in Kaliningrad, and numerous other disputes. Both countries are set to modernize their nuclear arsenals — and to many observers, it appears that the US and Russia are throttling toward a new Cold War.

On the surface, the election of Donald Trump might seem to offer hope for this foreboding international situation. Trump has generally been dovish on Russia, far more so than the US foreign policy establishment. His election was praised by Putin as an opportunity for re-engagement [3]— and presumably a restoration of diplomacy could include arms control talks. As Ploughshares Fund grantee Hans Kristensen noted after Trump’s victory, Republicans do have a much better record on nuclear arms reduction than Democrats [4]. Could the Trump-Putin rapport ultimately result in something positive?

At this early stage, the only honest answer is — maybe. But there are reasons to temper any initial enthusiasm. For starters, outsourcing arms control to two nationalists with a penchant for militaristic posturing seems like a bit of a fool’s errand. More concretely, the Trump transition website displays nothing but enthusiasm for the $1 trillion nuclear modernization plan [5] the president-elect inherited from Obama.

We don’t know much about who in the Trump administration will be overseeing nuclear policy, but what we do know isn’t particularly encouraging. It’s true that Gen. James Mattis, Trump’s pick for Defense Secretary, has questioned the need for land-based ICBMs [6], but Mattis’ unorthodox views seem unlikely to find widespread support in the administration. The Heritage Foundation, whose influence on the Trump team has been well documented [7], is strongly in favor of modernizing the entire nuclear triad [8]. And Mira Ricardel, the head of Trump’s Pentagon transition team, was previously an executive in Boeing’s Strategic Missiles and Defense division. Her appointment may indicate full administrative backing for the new ICBM [9], a modernization program that others, presumably including Mattis, regard as ripe for cancellation. Trump’s personnel choices may be sending mixed messages, but it seems doubtful that the administration as a whole will be receptive to traditional DC-driven arms control initiatives.

As for the defense industry, it clearly didn’t expect Trump to win (supporting Clinton by a 2–1 margin [10]), but after his victory defense stocks soared nonetheless [11]. Trump recently singled out the F-35 joint strike fighter for cost overruns, but so far the defense industry doesn’t appear concerned that similar criticisms might be lobbed at nuclear weapons programs. If arms reduction is a possibility under Trump, defense contractors aren’t worrying about it. And why should they? Nuclear hawks are already taking to the pages of the Wall Street Journal [12] to call on Trump to expedite the modernization of the US arsenal. It certainly looks like there are boom times ahead for the private corporations that make up the United States’ “nuclear enterprise.”

More worryingly, legitimate questions were raised during the presidential campaign about Trump’s temperament, his knowledge of basic nuclear weapons policy, and his apparently blasé attitude toward nuclear proliferation. Now, like all US presidents, Trump can launch a nuclear weapon at a moment’s notice without a hint of democratic oversight. This fact has many Americans on edge — understandably.

So on the one hand, we have a president-elect who has spoken about nuclear weapons in a manner that many regard as disturbingly cavalier. On the other, a defense industry that is positively giddy over imminent increases in spending on nuclear weapons. And all of this is happening at a time of immense global instability, when relations between the two major nuclear-armed states are extraordinarily fraught and the risk of miscalculation is high.

If this sounds familiar to you, it should. It’s common right now for media reports to declare that US-Russian relations are at their lowest ebb since the Cold War, which is certainly true. But what is rarely elaborated is when, exactly, that last low point occurred. It was, without a doubt, during the first few years after the landmark election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. Although relations between the superpowers had been spiraling downward during the second half of the Carter administration, Reagan’s first term was truly a nadir of the Cold War, a moment when nuclear war seemed like a very real, even a likely, possibility. It was also a coming out party for nuclear weapons hawks: a point when disarmament proponents were locked out of government and the prospects for arms control seemed gloomy at best.

Obviously there are differences between Reagan and Trump, particularly their divergent perspectives on Russia. And Vladimir Putin’s Russia is not the Soviet Union [13], despite the seemingly interminable number of articles making that claim. Still, there are some important lessons to be learned from comparing the present moment to the early 1980s. The nuclear freeze movement’s response to Reagan offers an alternative to beltway politics, a way of reigniting the push for disarmament from outside a Trump administration that is ill-inclined to listen and a Putin government that is pursuing its own modernization agenda. As a historical parallel to the contemporary moment, the early 1980s demonstrates the immense benefits of pressing our aims from beyond the blocs — which are after all united in their allegiance to weapons that threaten to plunge our world into unparalleled catastrophe.

The Late Cold War Heats Up

These days, Ronald Reagan is celebrated across the political spectrum for being a nuclear abolitionist who engaged with the Soviets and helped pull the world back from the brink of apocalypse. There is some truth to this story. Reagan did express, both publicly and in private, a personal opposition to nuclear weapons. But that famous line of his — “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought” — was uttered in response to enormous public pressure that built up against the arms race during his first term. As documented in an excellent dissertation (and now book [14]) by historian William M. Knoblauch, this line was part of a multifaceted public relations push by the administration to rebrand Reagan as a measured and peaceful leader.

And why was this rebrand necessary? Because people were terrified of him — and the many nuclear hawks he appointed to positions of power. Members of his administration, and occasionally Reagan himself, talked openly about fighting and winning a nuclear war. Journalist Robert Scheer, who was then covering nuclear weapons issues for the LA Times, wrote an entire book about it, with one of the most notorious statements giving the volume its provocative title [15]. It’s well known that Reagan took a dim view of federal spending, but there was a major exception to this rule: he repeatedly raised the defense budget and particularly prioritized nuclear weapons. Reagan’s spending on nuclear weapons research, development, testing, and production represented a 39% increase over the previous eight years [16].

The administration’s loose talk about nuclear war and military spending bonanza were happening at a time when US-Russian diplomacy had completely broken down. The two superpowers were barely speaking to one another. This chilly diplomatic situation was made worse by the fact that the USSR went through three leadership changes — all due to deaths, basically from old age — between 1982 and 1985. Konstantin Chernenko, the last guy to occupy the top post before Mikhail Gorbachev, was seriously ill when he became General Secretary and barely made it a year before succumbing to, among other things, emphysema, hepatitis, congestive heart failure, and cirrhosis of the liver. When he heard the news, Reagan apparently asked, “How am I supposed to get anyplace with the Russians if they keep dying on me?” It’s a legitimate question, to be fair to the Gipper.

At the same time the USSR was constantly reshuffling its leadership, the KGB became convinced that the US was planning a nuclear first strike [17] — and ordered its operatives in the US and Western Europe to stay on the alert for signs of a preemptive attack. In Washington, DC and elsewhere, Soviet agents went so far as to count the number of lights left on in government buildings at night, trying to read them prophetically like tea leaves.

The KGB, like all intelligence bureaucracies, had a vested interest in hyping up security threats, but it’s hard to deny that the global situation in the early 1980s was deeply unstable. To briefly sketch the geopolitical environment, there were Cold War proxy conflicts in Afghanistan, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Grenada, Angola, and beyond. Poland was under martial law. NATO deployed nuclear cruise missiles and Pershing IIs to Western Europe. Reagan referred to the USSR as an “evil empire” and soon after announced the Strategic Defense Initiative.

Then, in September 1983, Soviet fighter jets mistook Korean Airlines Flight 007 for a US reconnaissance aircraft and shot it down, killing 269 people. Afterwards, Reagan cited the event as a reason US legislators should vote for the land-based ICBM MX missile — also known as the “Peacekeeper.” And in November of 1983, the US and NATO embarked on Able Archer 83 [18], a 10-day wargame so realistic that the USSR thought it might be a pretext for an actual nuclear strike (remember, they were expecting one) and put their forces on alert. With the possible exception of the Cuban Missile Crisis, those 10 days may have been the closest our world has come to thermonuclear war.

Freezing the Arms Race

Looking back, it seems miraculous that humanity even made it out of the early ’80s. So how did we?

In short, people took a stand. They refused to cede control of their fates to the leadership of the two superpowers.

The story we tell about the end of the Cold War is overwhelmingly one of high politics, a kind of bilateral Great Man Theory of History. In this narrative, Reagan and Gorbachev are depicted as forward-thinking leaders who defied the momentum of the arms race (and their own political sympathies) to deftly negotiate arms reductions and even flirt with total nuclear disarmament. Just like Reagan’s personal opposition to nuclear weapons, there is some truth to this story. But long before Gorbachev was even in office, millions in the US and worldwide were voicing their opposition to nuclear weapons, which they overwhelmingly associated with the Reagan presidency — both in the streets and at the ballot box.

In June of 1982, at least 750,000 people — and quite possibly one million — rallied in Central Park to demand an end to the arms race. It was likely the largest political gathering in US history. The consensus demand was for a bilateral freeze on the production, testing, and deployment of nuclear weapons. The idea had been spreading like wildfire since 1980, when cities, counties, and locales across the country began passing ballot initiatives in favor of a nuclear freeze. In the November 1982 elections, freeze initiatives passed decisively in eight states, including traditionally conservative ones like Montana and North Dakota. That year, 18 million Americans voted on the issue, with a resounding 60% voting in favor. Massachusetts Congressmen Edward Markey called it “the closest our country has ever come to a national plebiscite on nuclear arms control.” National polls showed an even higher level of support: the freeze repeatedly polled with an approval rate of 70% or more.

Almost overnight, the nuclear freeze had gone from being a fringe idea to a mainstream policy position debated in the media by pundits and politicians alike. This was in part a response to the genuinely dire international situation but also the result of dedicated grassroots organizing by people like arms control advocate Randall Forsberg [19], who seized upon the freeze idea as a strategy to move nuclear disarmament back into the political mainstream.

But for every public face of the freeze, there were also thousands of anonymous, average people actively involved in the campaign — and millions more passively supporting it. Participating organizations helped educate the public on nuclear war and an entire apparatus of counter-expertise was constructed to combat the dominance of defense intellectuals. Even language became a battleground, as activists pushed back against the cold, detached “nukespeak” of the defense establishment, replacing it instead with a discourse emphasizing the impact of nuclear war on the human body and even on humanity as a collective species.

The freeze policy was hardly radical. Forsberg quite consciously eschewed the longstanding promotion of unilateral disarmament in favor of an explicitly bilateral approach. The idea was that the two superpowers would jointly — and verifiably — pause the arms race as a first step toward reductions on both sides. From its inception, the campaign branded itself as moderate, middle class, and non-partisan. Instead of Washington, DC, it put its base of operations in St. Louis: literally “middle America.”

And yet, this did not stop freeze advocates from being denounced as fifth columnists, “useful idiots,” and Soviet sympathizers. For instance, the context of Ronald Reagan’s “evil empire” speech [20] in March 1983 is rarely brought up, but he uttered the infamous phrase while lambasting the freeze policy and its proponents. Reagan scolded freeze activists for placing equal blame on both sides of the Cold War, getting in the way of practical arms control measures (sound familiar? [21]), and engaging in “wishful thinking about our adversaries.” He also accused freeze advocates of “appeasement,” which is about as loaded a term as you’re going to find in foreign policy discourse. This was not an isolated incident: five months earlier Reagan had declared that the freeze campaign was “inspired not by sincere, honest people who want peace, but by some who want the weakening of America and so are manipulating honest people and sincere people.” The clear implication was that the freeze policy was part of a dastardly plot to subvert the United States from within.

In addition to fielding attacks straight from Reagan’s bully pulpit, the freeze movement came under relentless fire from conservative organizations, right-leaning newspapers, and prominent defense intellectuals. But in the face of this smear campaign, activists kept at it — and began to get results. Their successes were little acknowledged at the time, but in hindsight historians and social movement scholars have come to agree that the freeze movement (and its international counterparts in continental Europe and the UK) served as a powerful check on Reagan’s arms buildup. Millions of disarmament activists worldwide helped put his administration on the defensive, forcing the nuclear hawks to temper their rhetoric and return to the negotiating table with the Soviets.

Some of these changes were initially more about image management than true shifts in position: but the situation was then so bleak that even these cosmetic changes had significant ramifications for US-Soviet relations. Today Reagan and Gorbachev get the bulk of the credit for ending the arms race, but millions of common people set the stage for their breakthroughs. It is these unsung protagonists that pulled us back from the brink of nuclear war. Without the pressure they applied, who knows what would have happened.

Two Lessons

So what are the lessons of this historical parable? Two come to mind and believe it or not, they both offer hope at a time of widespread pessimism.

It is true that nuclear dangers persist and could intensify in time, but the first lesson is that things have been worse. There are genuine reasons to be frightened right now, whether you are concerned about Putin, Trump, or a symbiosis between the two that may have its own worrying momentum. But while the current international situation is dismal, it’s nowhere near as explosive as the early 1980s.

Today we have fewer nuclear weapons and fewer sites of proxy conflict. Russia and the United States are modernizing their nuclear arsenals but at least they aren’t expanding them. The challenge of the present is to restore the trajectory toward global zero — a far more manageable aim than attempting to halt a multi-decade arms race in perhaps the most dangerous period of the Cold War.

The longstanding norms against nuclear weapons testing and proliferation will not go gently into the night, whatever the relationship between Russia and the US. New social movements can build upon these norms to push back against nuclear modernization, which, although it does not produce more warheads, does reaffirm both states’ commitment to nuclear weapons for the foreseeable future. Challenging this state of affairs will be difficult, but disarmament proponents can at least take some comfort knowing we will not face the long odds that confronted activists in the Reagan era.

The second lesson follows from the first: change is absolutely possible. There is nothing inevitable about nuclear war or nuclear weapons themselves. The US and Russia are not doomed to stumble inexorably toward the apocalypse and neither is the planet as a whole. Thanks to the efforts of movements like the freeze, in the 1980s the world went from the depths of nuclear despair to major reductions in global arsenals in just a few years. Activists accomplished this while being derided by the president, treated with condescension by defense experts, and slandered as traitors by hawkish commentators. The peace movement of the early Reagan period faced a foreboding environment both at home and abroad — but brought about major political change anyway.

The geopolitical situation today is similarly ominous, but there are reasons for genuine optimism. In October, the UN passed a historic resolution to begin negotiations toward a ban on nuclear weapons: not sometime in the distant future, but in the coming year. The vote was a major rebuke of the nine nuclear-armed states and an unqualified victory for global democracy. It follows several years of internationalist organizing based around the humanitarian impact of nuclear war — and demonstrates that grassroots activists, civil society groups, faith-based organizations, and non-nuclear states can form a coalition to counteract the entrenched power of the “nuclear oligarchy,” [22] which is led by the United States and Russia. The momentum on the global stage is promising: arms control advocates here in the United States would be wise to throw their support behind the UN ban treaty initiative.

On the domestic scene, there are other reasons to be positive. The last several years have seen an explosion of new social movements dedicated to a wide variety of issues, from police violence to inequality to climate change. The young activists involved in these campaigns are dedicated, informed, and media savvy. They are not going to cease fighting simply because of an adverse political environment and neither should we. In the nuclear weapons arena, grassroots disarmament organizations are already strategizing for the next several years of being out in the wilderness. If they can make connections across political struggles, linking nuclear arms reductions to other progressive aims, the potential for popular mobilization is huge.

In fact, this is an area where a new movement can actually improve upon the freeze model. The freeze campaign was designed to be a “respectable,” middle class movement, but in practice this strategy tended to marginalize the views of people of color and members of the working class. To shore up its moderate image, the freeze campaign largely sidestepped related questions of redistribution and social justice, a critical error at a time of major political-economic upheaval. With slight alterations to its model of organizing, the freeze movement could have been even more powerful, capable of resisting not only the arms race, but the broader set of regressive policies now associated with the “Reagan revolution.”

Go Outside

Being shut out of the halls of government is understandably maddening, especially at a time of profound international crisis. But politics does not reside solely within the DC beltway and history demonstrates the many benefits of an outsider approach to nuclear arms control. Sheer necessity may have brought us to this point, but a revival of the disarmament movement is precisely what is needed to push back against the juggernaut of nuclear modernization, which has always had robust bipartisan support. A renewed movement will also circumvent the ambiguities of the Trump-Putin relationship, which cannot be passively relied upon to ease international tensions and reduce US and Russian arsenals.

Uncertainty reigns on both the domestic and the global stages. But as the nuclear freeze movement shows, gloomy futures can be very motivating. Through dedication, organizing, and an embrace of the outsider status that seems to have been thrust upon us, the momentum toward a world without nuclear weapons can be reignited and sustained. The task may be daunting, but few goals are more essential for our planet and its citizens. We have inherited this task from grassroots movements like the freeze — and it is high time to finish the job they worked so hard to begin.

By John Carl Baker, PhD, a Mellon-ACLS Public Fellow here at the Ploughshares Fund

Photo: Nuclear freeze campaigners in San Francisco, 1982. Credit: It's About Times courtesy of FoundSF [23]

Arms Control in the Age of Trump: Lessons from the Nuclear Freeze Movement.

Post to Twitter [24]