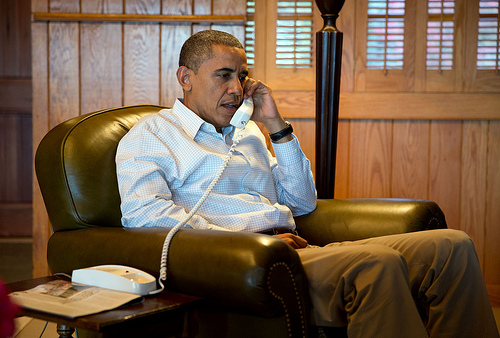

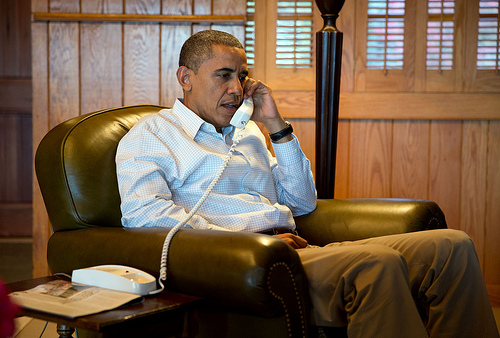

obama_0.jpg [1]

President Obama’s administration portrayed the 2010 nuclear arms reduction treaty—which provides modest cuts to US and Russian strategic arsenals—as a means to “prime the pump” to achieve deeper and more comprehensive cuts down the road. But after enduring a grueling fight with Senate Republicans to ratify the treaty, the administration decided to table new talks with Russia until after the 2012 presidential elections, when the new political environment would make an agreement easier to achieve.

But election year politics is not the only obstacle to achieving a more comprehensive nuclear arms treaty. An agreement that seeks further reductions in deployed strategic nuclear weapons and fresh cuts to non-deployed and tactic weapons is likely to encounter significant objections from Russian realists and Senate Republicans alike. And when President Obama’s pragmatic national security team considers the stiff headwinds an agreement is likely to face, they may opt for unilateral but reciprocal cuts that achieve some of their arms control objectives, while minimizing the chances that the initiative gets derailed entirely.

The first challenge the administration will encounter is finding common ground with their Russian counterparts, who are not as enthusiastic about deeper cuts. Many Russian officials believe a robust nuclear force is a matter of national security and international prestige. From Moscow’s perspective, nuclear weapons are a means to offset the West’s superior conventional military capabilities. Russia places particular importance on its tactical nuclear arsenal—which is about ten times the size as America’s non-strategic stockpile—because it provides a deterrent to potential regional threats from NATO countries and China. This imbalance in tactical weapons will likely be a primary sticking point in new talks.

Moscow will also likely insist on some kind of limitation to the US missile defense program, which the Russian’s perceive as an offensive threat. Russian President Vladimir Putin this summer issued a foreign policy directive noting the importance of “seeking firm guarantees that the (US missile defense program) is not aimed against the Russian nuclear force.” But any meaningful constraints on missile defense would almost certainly make an agreement unratifiable in the US Senate.

In fact, the Senate may present the greatest obstacle to achieving a new arms-reduction treaty. Many congressional republicans are ideologically opposed to an agreement that constrains—in any capacity—US defense. Out-going Republican Senator Jon Kyl, who was the administration’s biggest opponent on arms control during the NEW Start ratification, is strongly opposed to President Obama’s vision of a nuclear-free world. In 2010 he asked rhetorically: “Is ‘zero’ really desirable? Nuclear deterrence has kept the peace between superpowers since the end of World War II…are nuclear weapons really a risk to peace or a contributor to peace?”

Many of Kyl’s Senate colleagues share his view and will likely resist efforts to lower ceilings on the US nuclear arsenal. They will likely also oppose Russia’s efforts to link nuclear weapons reductions and US missile defenses.

Given all these potential obstacles, it is hard to envision a treaty that achieves compressive reductions and is capable of winning the support of Moscow and the US Senate. Settling on an agreement with Moscow might take several years, meaning the administration will miss the small political window it has to push through an agreement. And if Senate Republicans dig in their heels, the administration may face a prolonged battle on the Hill.

Is President Obama willing to expend substantial political capital on nuclear arms reductions at the expense of domestic priorities?

When Obama’s pragmatic national security team assesses the lay-of-the land, they may choose an easier option: reciprocal cuts. Arms control has not always been achieved with treaties. In 1991, President George H. W Bush and Russian President Mikahail Gorbachev made substantial reciprocal cuts to tactical nuclear weapons.

Such an approach would have several advantages. First, it does not require Senate ratification, taking the intransigent Republicans out of the picture. It also gives each side more flexibility to reduce their stockpile in a manner that does not compromise security. In particular, it would not require Russia to maintain comparable limits on tactical weapons. Of course, such an approach comes with disadvantages, most notably that it likely would not allow a robust verification regime.

Opting for unilateral cuts instead of a comprehensive treaty might be a hard pill for the administration to swallow, but it is probably the President’s best chance of making good on his promise to achieve sweeping weapons reductions.

This blog post was authored by Ian MItch, a graduate student at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service. He is a member of a seminar on Nuclear Policy and International security taught by Joe Cirincione.

Links

[1] https://ploughshares.org/file/2885

[2] http://www.flickr.com/photos/whitehouse/8109943266/in/photostream