In the United States, anything nuclear is inherently presidential. Any change in nuclear policy requires presidential leadership and sustained engagement. Moreover, decisions to pursue new initiatives must be made early in a new administration, and then executed over a number of years. Coming late to the nuclear policy party — or just stopping by — is usually a recipe for frustration and inaction.

The issue of whether the United States needs to continue to store tactical nuclear weapons in Europe will be no different. Changing the nuclear status quo in NATO will require the early and sustained leadership of the next US president. Moreover, the clock is already ticking: with the next NATO summit looming in 2017, the next administration will need to take the initiative early in their first term, before the cement of NATO summitry and bureaucracy hardens around their legs for the next four years.

Today, there is a compelling case for NATO to move to a safer, more secure and more credible nuclear deterrent — without basing US tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. That case begins with a recognition that sustaining NATO’s current nuclear posture is an expense that (a) NATO members need not incur to maintain a credible nuclear deterrent; and (b) will increasingly undercut efforts to sustain credible conventional capabilities across NATO. Furthermore, the security risk of basing US nuclear bombs in Europe — highlighted by the recent terrorist attacks in Belgium and political developments in Turkey — clearly demonstrate the case for consolidating US nuclear weapons in the United States.

An Expensive, Out of Date and Dangerous Status Quo

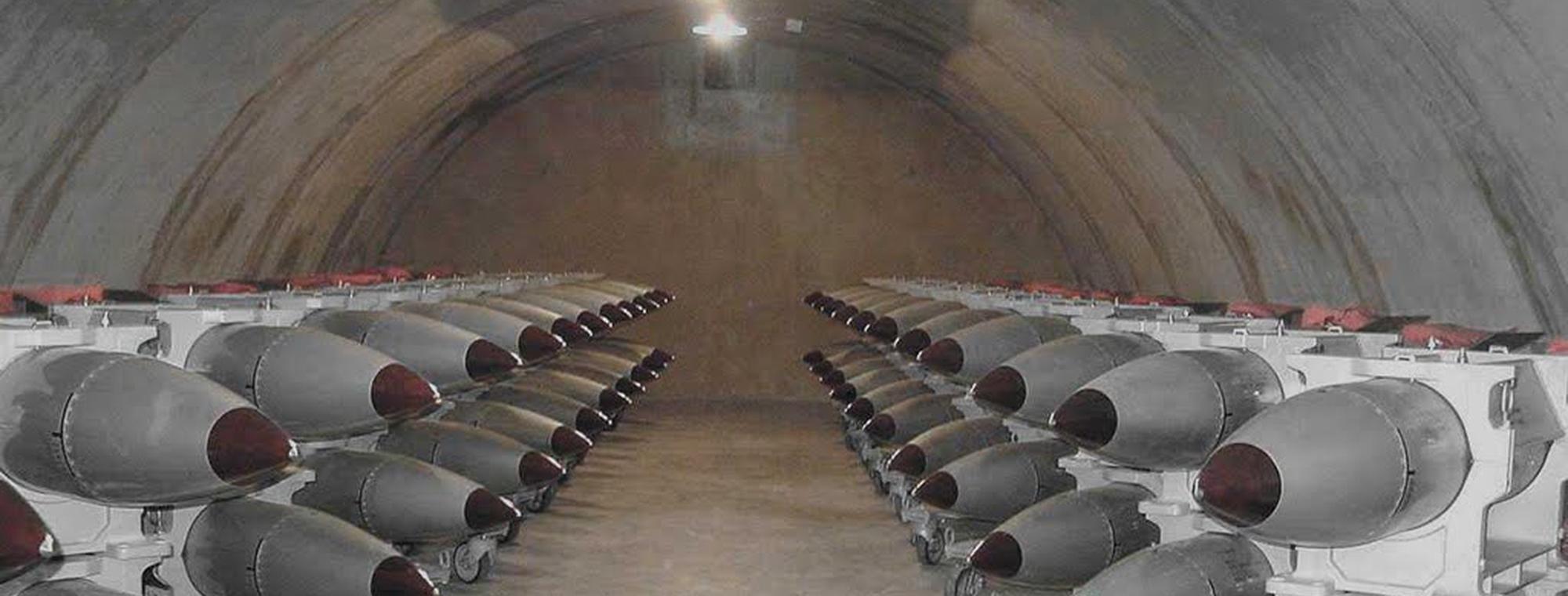

The B61 life extension program (LEP) now underway in the United States is intended to replace the B61 bombs stored in Europe with a new variant, the B61-12. This program was originally justified as a cost-effective means to upgrade the safety and security of the weapons while preserving US extended deterrence commitments to NATO allies. However, estimated costs have risen significantly from $4 to $13 billion, which for only 400-480 bombs could make this the most expensive nuclear weapon ever built. (1)

The Obama administration has strongly supported the B61 LEP; nevertheless, some have questioned whether the modified B61’s increased accuracy and limited earth-penetrating capability constitutes the development of a new, more usable nuclear capability. This has raised concerns that military commanders might be more willing to recommend using the bomb based on the questionable assumption that the radioactive fallout and collateral damage would be limited. This could reopen uncomfortable debates over nuclear use policy in many of the host countries, à la the neutron bomb in the 1970s.

More broadly, there has been little in the way of public discussion and even less debate about what alliance missions the B61-12 has been designed to address that cannot be accomplished with other US nuclear and NATO conventional capabilities.

The argument that these weapons, first deployed in Europe in the early 1950s, play a deterrent role that cannot be fulfilled today by US strategic weapons or conventional weapons has been refuted by a number of military experts, including the former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under President Barack Obama. (2) In order for any weapon to be credible as a deterrent, its use must be plausible; otherwise, it has no political utility as a deterrent. Even taking into account what some perceive to be a more “usable” weapon, it is hard to envision the circumstances under which a US president would initiate nuclear use for the first time in over 70 years with a NATO dual-capable aircraft (DCA) flown by non-US pilots delivering a US B61 bomb. It is equally hard to envision host-country governments authorizing their aircraft to deliver the weapon. And according to at least one former NATO commander, it is hard to envision any mission succeeding even if ordered, given the political and operational constraints involved. (3)

There are also questions relating to the status and expense of maintaining and eventually upgrading DCA in NATO countries that reportedly host the B61. The nuclear sharing mission is not popular among publics or certain political parties and parliamentarians in host countries, and none of these countries has so far publicly discussed its decisions relating to enabling any DCA replacement aircraft to carry nuclear weapons. It is also not clear who will pay the extra costs to make the aircraft dual-capable. While cost figures are not publicly available, they are expected to be significant, and governments will likely face opposition in getting the consensus necessary to invest in a commitment that will sustain the nuclear mission in their countries for decades to come.

On the conventional side of the deterrence ledger, given the strong possibility that Vladimir Putin will remain president for another eight years, a long term response to Russian security policy in Europe will likely require the US to commit to conventional reassurance plans beyond the $3.4 billion tagged for 2017 (which was already four times 2016 spending). This new spending will have to be sustained against the backdrop of continuing demands for even more from certain NATO members — and continuing fiscal constraints across NATO.

Another new and increasingly alarming consideration in continuing to base US nuclear weapons in Europe is the risk of a terrorist attack against a European NATO base. The US Air Force cited deficiencies in the security of US nuclear weapons stored in Europe in a study a few years ago, and former senior NATO officials have also raised concerns. US Air Force General Robertus C.N. Remkes, who commanded the 39th Air Base Wing at Incirlik Air Base and later J5 EUCOM, wrote in 2011 of the severity of the political and security consequences of any infiltration of a site for the alliance, whether or not the attackers gained access to the weapons themselves. (4)

More recently, in March 2016, the Pentagon reportedly ordered military families out of southern Turkey, primarily from Incirlik Air Base, due to ISIS-related security concerns. This report came shortly after the Brussels terrorist attacks and what appears to have been a credible threat to Belgian nuclear power plants. In July, we saw the Turkish commanding officer at Incirlik arrested for his alleged role in the Turkish coup plot. If reports are accurate — that Incirlik is a major NATO installation hosting US forces that control one of the largest stockpiles of nuclear weapons in Europe — this shows just how quickly assumptions about the safety and security of US nuclear weapons stored abroad can change literally within minutes, adding another layer of security concern.

Changing the Status Quo

One thing is certain: any change in NATO’s nuclear status quo will begin in the White House, and not at NATO headquarters in Brussels. The next president of the United States will need to take charge of this issue if he or she wants to move NATO towards a safer, more secure and more credible nuclear posture — without the expense, opportunity cost and risk of basing US nuclear weapons in Europe.

Easier said than done? Of course. But it is also true that the next president can, and should, get this done by carefully leading — and working with — NATO. The trick is knowing when and how to lead — and when and who to work with.

First, it will be important for the next president to take the first step with allies months before the next NATO summit in 2017. Springing a new initiative on NATO days before, or even at, the summit is counter to how NATO works, and counterproductive to getting change done.

Second, the first step taken by the administration should be comprehensive, and not incremental. The president needs to lay out a vision and rationale for moving towards a safer, more secure, and more credible nuclear deterrent — and explain in broad terms why and how this can be done to improve the security of all NATO members. In brief, the president would say something along these lines:

- I am committed to maintaining a safe, secure and credible NATO nuclear deterrent for as long as one is needed; and I am committed to sustaining conventional reassurance initiatives to meet any challenge to NATO’s security.

- Both of these crucial objectives can be better achieved without the expense, opportunity cost and risk of basing US tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. I will therefore consolidate all US tactical nuclear weapons now stored in Europe in the United States.

- At the same time, the United States will work closely with NATO allies to strengthen NATO’s overall deterrent and defense capabilities, both nuclear and conventional.

- With respect to nuclear deterrence, the United States will work closely with NATO to restructure NATO’s nuclear deterrent so that it is safer, more secure, more credible and more affordable. This will include: maintaining the strategic nuclear forces of the alliance, along with a more visible demonstration of the security guarantee provided by these forces to European allies; and enhancing information sharing, consultations and planning.

- With respect to conventional deterrence, the United States will devote a portion of the savings associated with consolidating US tactical nuclear weapons back to the United States, and scale back the US B61 modernization program to conventional reassurance over the next five years.

Third, the “NATO process” should then be used not to “review,” but rather to “implement” the president’s vision. No new NATO strategic concept or deterrence and defense posture review is needed. Indeed, these NATO-led reviews are often the graveyard for initiatives, large and small.

This is not to say that NATO does not, or will not, have an important role to play. NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group should be given a clear mandate in 2017 to develop and recommend to ministers and leaders how existing nuclear sharing, consultations and planning can be enhanced across NATO, and how NATO can visibly and more credibly demonstrate that it remains a nuclear alliance.

Fourth, it will be important for the president to work with Congress to ensure the smooth implementation of this initiative, including continued funding of conventional reassurance initiatives. Up until now, the Obama administration’s conventional force enhancements for Europe are being funded from an offbudget, war-fighting account meant for Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan. This avoids having to make difficult trade-offs in the Pentagon budget, and may prove unsustainable beyond 2017. The next president and Congress can and should seek to provide greater predictability and permanence regarding our commitment to bolster NATO defenses.

Finally, the next president will need to confidently make the case that it is important for NATO leaders to stop acting on the dangerous idea that mirror imaging Russian actions, in particular in the case of nuclear weapons, equates to sound security policy. Yes, Russia has retained and is now modernizing its inventory of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. But with the United States, Britain and France, it is also true that NATO has a robust nuclear deterrent and does not need to invest in tactical nuclear weapons. In fact, NATO has a range of other defense priorities, including terrorism, migration and cybersecurity, that will demand greater attention and effort in the years ahead.

That’s a message that NATO countries need to hear from our next president — and, for their own security, the sooner the better.

Steve Andreasen is a national security consultant to the Nuclear Threat Initiative and its Global Nuclear Policy Program in Washington, DC, and teaches courses on National Security Policy and Crisis Management in Foreign Affairs at the Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota.

Isabelle Williams is the senior adviser to the Global Nuclear Policy Program at the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

Notes:

1 The total B61-12 program cost varies widely. It was originally assessed at $4 billion in 2011. In 2012, an independent assessment by the Pentagon’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation office assessed the program at a $10 billion with an additional $1 billion for the Tail Kit Assembly. In 2015, the National Nuclear Security Administration and Department of Defense estimated the total life cycle cost at $8.9 billion. Additional independent estimates put the B61-12 at $13 billion.

2 James Cartwright, et al., “Global Zero US Nuclear Policy Commission: Modernizing US Nuclear Strategy, Force Structure and Posture,” Global Zero, May 2012.

3 Karl Heinz-Kamp and Robertus C.N. Remkes, “Options for NATO Nuclear Sharing Arrangements,” in Reducing Nuclear Risks in Europe, eds. Steve Andreasen and Isabelle Williams (Washington, DC: Nuclear Threat Initiative, November 2011).

4 Robertus C.N. Remkes, “The Security of NATO Nuclear Weapons: Issues and Implications” in Reducing Nuclear Risks in Europe, eds. Steve Andreasen and Isabelle Williams (Washington, DC: Nuclear Threat Initiative, November 2011).

Photo: B61 nuclear bombs in storage. US Government photo

Bring Home US Tactical #NuclearWeapons from Europe @NTI_WMD.