Story Center

Current news and exciting stories highlighting the good, the bad, and the truth about nuclear weapons in the world.

The Big Story

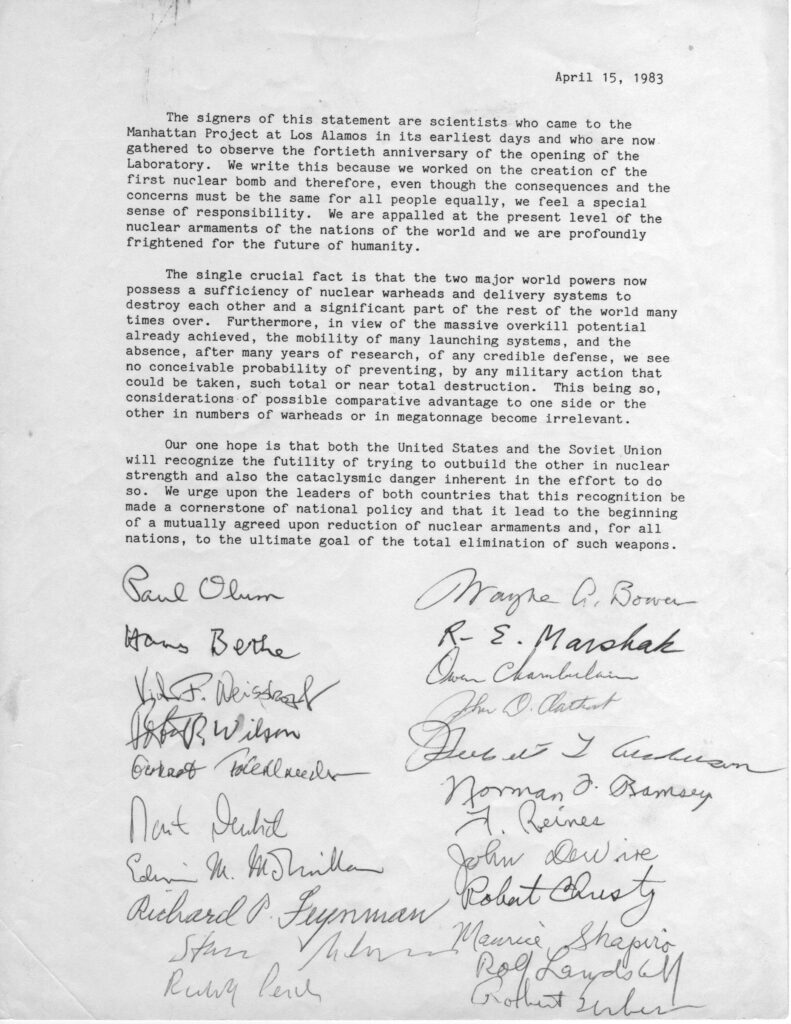

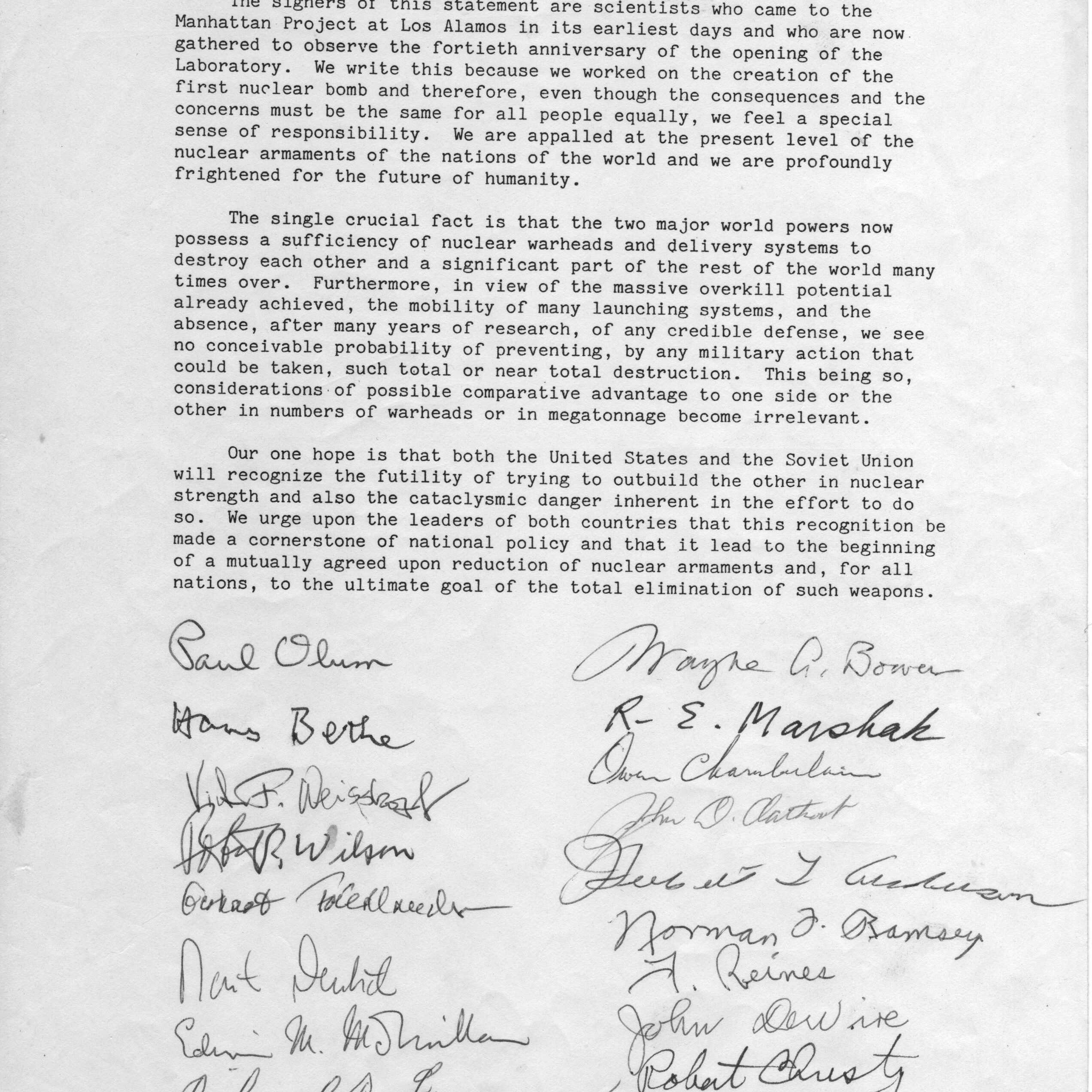

Stopping Nuclear Inevitability

Dr. Emma Belcher was recently a guest on PBS's 'The Open Mind' discussing how to reverse the likelihood of nuclear war.

Please contact Charles Crosby at ccrosby@ploughshares.org for further information on any of these stories or to arrange for interviews.