A new war with Iran is not what the American people want. President Trump has no clear objectives and no Congressional approval.

His military threats against Iran only make successful diplomacy a more distant prospect while military action would risk needless Iranian and American casualties in service of a conflict that threatens US interests and regional stability.

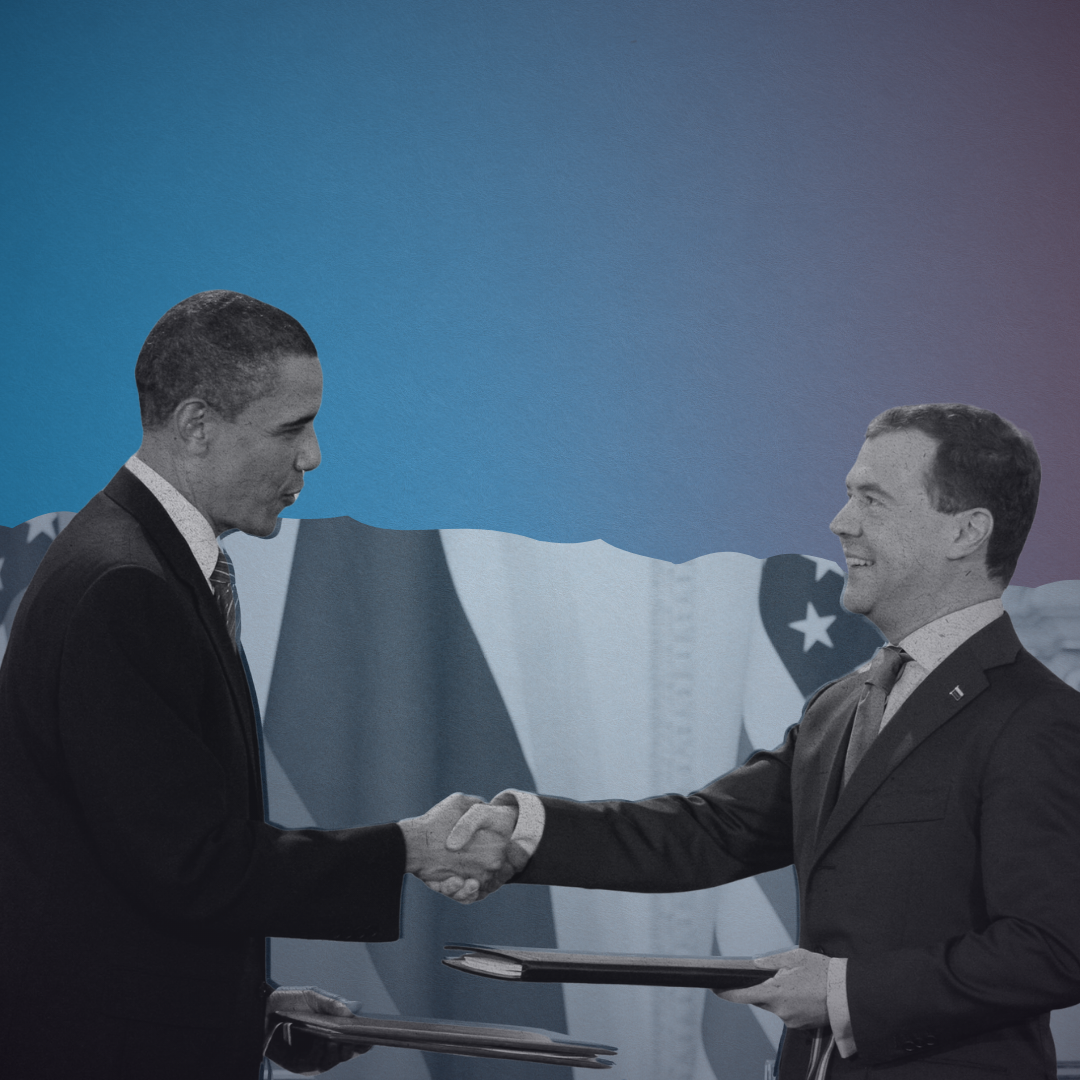

Iran’s nuclear program cannot be eliminated through military force. Only serious negotiations can produce a deal that blocks an Iranian pathway to the bomb. The administration should pursue good-faith diplomacy & heed the American public’s call to avoid another war with Iran.