The US and Israel have begun a senseless, unprovoked, and illegal war against Iran, with no viable plan for its conclusion. This conflict could unfold with incomprehensible losses for innocent civilians across the region.

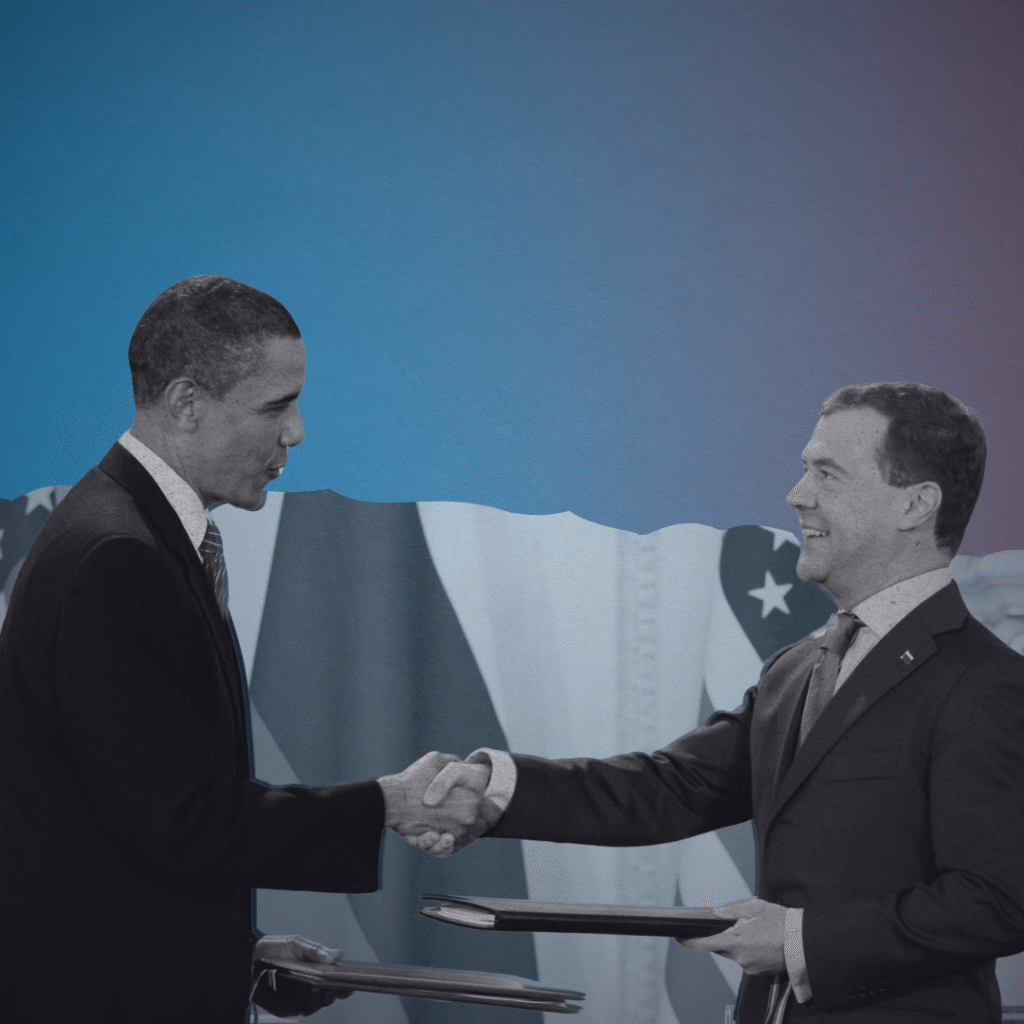

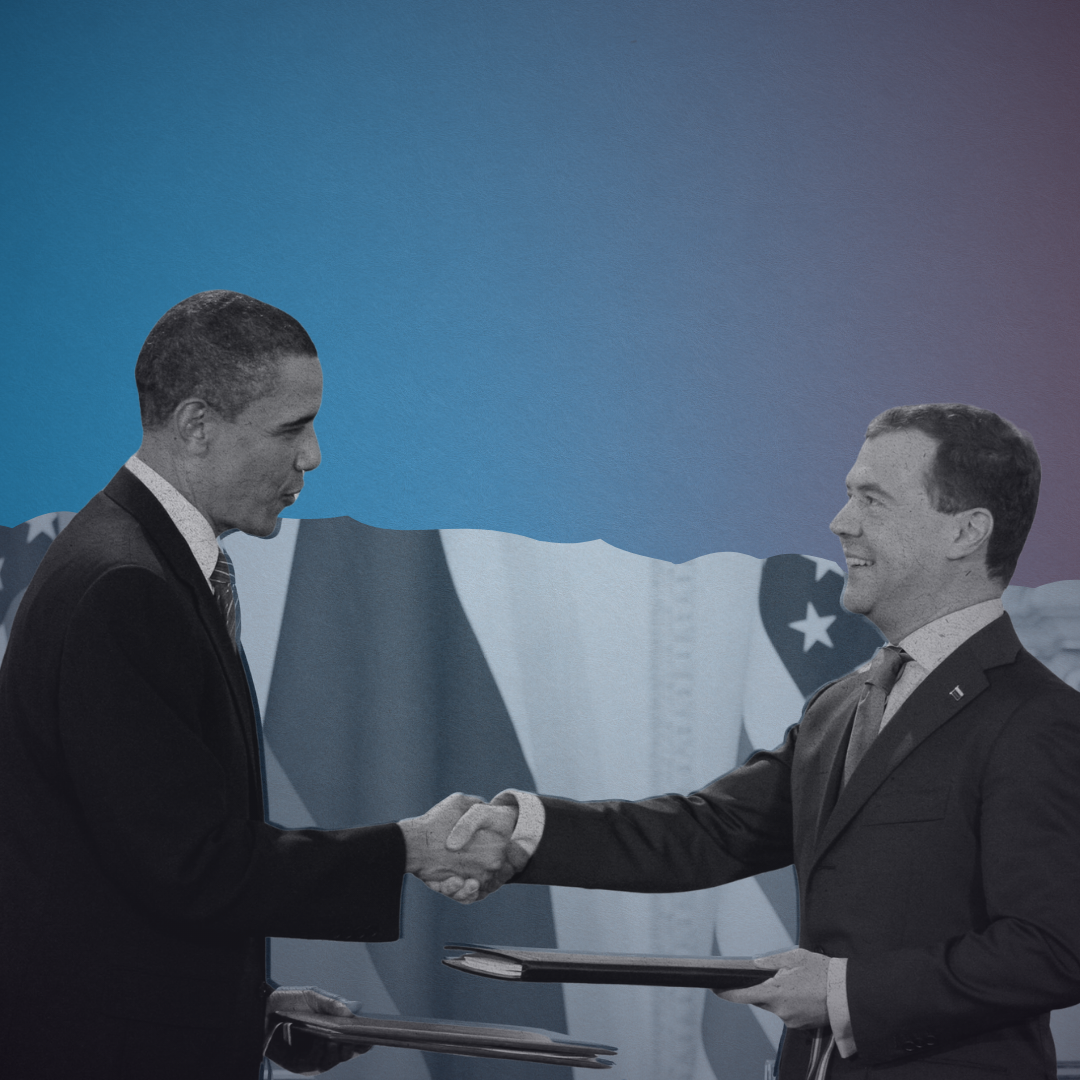

The American people oppose this war, and the US Congress did not approve it. At Ploughshares we have long fought for meaningful diplomatic agreements to prevent Iran from becoming a nuclear-armed state. A previous agreement to accomplish this goal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, was working when President Trump recklessly left it during his first term. A diplomatic solution to the nuclear issue has always been attainable, but President Trump has instead chosen the path of war for–by his own admission–regime change.

We must be clear-eyed: this is a war of choice. Congress must act now to stop further escalation before more lives are put at risk.